Articles

Articles

Remembrance Day: finding my grandfather and discovering his role in WWII

To coincide with Remembrance Day 2021, the AGHS is proud to

publish this article on Eddie Anderson, penned by his

granddaughter Vidya. Lest We Forget.

I grew up in Toronto, Canada with virtually no connection to my

family’s history.

In the 1970s, my parents emigrated to Canada – my father from

Indonesia by way of Holland and my mother from Australia. The

inheritance of every mixed-raced child is to have a foot in two

different worlds and a keen sense of never quite belonging.

Growing up as the mixed-race child of immigrants only increased my

sense of dislocation and isolation in a society where interracial

marriages were not the norm.

My parents did not talk much about their homelands or their

families, focusing instead as most immigrants did, on building a

new life here in Canada.

Learning about my heritage

As I grew older, I wanted to learn more about my heritage and my

place in the world, beyond the identity I had built for myself.

All I had to go on was “an Australian grandfather who golfed and

fought in WWII”. I didn’t even know his name.

When the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown began, I found myself mentally

stranded, so I ventured down the rabbit hole of genealogical

research. On my journey, I connected with an Australian golf

historian. He helped me uncover the story of my grandfather –

Eddie Anderson – a man who fought in the Pacific theatre of World

War II, a prisoner of war, and a PGA champion and Australian golf

legend.

Thailand-Burma “Death” Railway

My grandfather enlisted with the Australian Military Forces on

August 4, 1941. He served as a private in the Australian Light

Infantry’s Eighth Division. He shipped out to Singapore in 1942 to

the Johore defensive line. Shortly thereafter, Malaysia fell to

the Japanese. My grandfather was taken prisoner and forced to

build the Burma Railway connecting Bangkok (Thailand) and Rangoon

(Burma-Myanmar) to supply troops and weapons to the Japanese in

the Burma campaign.

It was known as the ‘Death Railway’, because over one hundred

thousand Allied prisoners and forced labourers died during its

construction from 1942 to 1944. Conditions were horrific.

Prisoners suffered and died from the working conditions,

maltreatment, sickness and lack of food, water, and medical

attention.

Eddie Anderson’s army attestation form (National Archives of Australia) (Click for larger image) |

Disaster at Sea

Somehow, my grandfather survived. Along with 1300 other prisoners

of war (POWs), he was loaded into the Rakuyō Maru, a prisoner

transport ship headed for Japan. It was part of a convoy

transporting Australian and British POWs, and other supplies for

the Japanese war effort, including oil, rubber, and bauxite.

Allied POWs called them “hell ships,” overloaded with POWs being

relocated to internment on the Japanese Home Islands or elsewhere

in the empire. The holds were floating dungeons, where inmates

were denied air, space, light, bathroom facilities, and adequate

food and water.

Thirst and heat claimed many lives in the end, as did summary

executions and beatings. Yet, most deaths came as a result of

“friendly fire” from U.S. and Allied naval ships, submarines, and

aircraft. The Allies sank other POW transport ships during 1944,

but the sinking of the Kachidoki Maru and the Rakuyō Maru on

September 12, 1944 led to the first eyewitness accounts being

given by former POWs to Allied administrations about conditions in

camps on the Thailand-Burma railway.

|

|

Identification photographs from

Eddie’s service file (National Archives of Australia)

Sinking of the Rakuyō Maru

In the early hours of September 12,1944, my grandfather’s ship was

attacked in the Luzon Strait by a wolfpack of three U.S.

submarines. Rivers of fire were blazing in the sea from the

convoy's oil tankers, hit earlier in the night. The men knew that

they needed to abandon ship.

There were few lifejackets and the Japanese had commandeered the

lifeboats, soon picked up by a Japanese destroyer at dusk. The

POWs threw anything in the water that would float. My grandfather

was thought to be lost at sea. Instead, he swam back to the

sinking ship and found something to eat before it sank.

Along with fellow Australian survivors, he waited until the

Japanese destroyer was out of sight and piled into an abandoned

lifeboat. After four days at sea, with little water to drink and

only mouldy rice, scrounged from a dirty tin in the bottom of the

lifeboat, to eat, my grandfather and his comrades were picked up

by two Japanese patrolling destroyers. The destroyers took them to

the Chinese port of Amoy where they waited in a whaling station to

continue their journey to Japan.

However, their trials were far from over as this new convoy was

also torpedoed and sunk. Amazingly, the whaling ship survived and

eventually arrived at Moogi, a southern port in Japan. My

grandfather was listed as missing in action and presumed dead for

five months.

Eddie Anderson’s service and casualty form (National Archives of Australia) (Click for larger image) |

Waiting for Armistice

For the next 10 months, my grandfather was forced to work in a

chemical factory and on the wharf. After more than three years as

a POW, my grandfather was liberated on September 13, 1945 and

shipped to Manila to convalesce. A month later, he arrived home in

Australia on the British aircraft carrier, Formidable. He was

awarded the 1939/45 and Pacific Stars, and the War and Australia

Service medals.

When I read his war record, the aging news articles, and military

historical accounts, I was stunned by his accomplishments and what

he survived. Putting all the pieces together didn’t just paint a

picture of incredible courage and fortitude but also of the grim

realities of the war.

Golf saved my grandfather’s life

My grandfather survived, but he came home with what my mum called

“shattered nerves”. Today, we would call it post-traumatic stress

disorder (PTSD).

Civilian life would see my grandfather return to his love of golf.

Before the war, he was a golf celebrity and professional, winning

the Queensland Professional Golf Association (PGA) championship in

1937 and 1938. His career was cut short when the war broke out and

he enlisted.

My grandfather should never have been able to pick up the game

again after what he endured, but he remained disciplined and

single-minded. Golf was his first love, after all. His theory was

that “…besides working at golf, you have to think of it to the

exclusion of all else – and dream of it too.”

Golf was his salvation. During the war, he kept himself in form in

Singapore and in the POW camps by swinging with tapered pick

handles, and the occasional club lent by Australian and Japanese

officers.

Less than a year after he was liberated, my grandfather returned

to golf in 1946, winning the Spalding Purse for the fifth time in

his career. He continued to be highly successful, culminating with

designing, building, and running his own golf course at Hudson

Park, with my grandmother Beryl Anderson.

My grandfather was steely, single-minded, and determined. He

survived World War II, came home a hero, and rebuilt an enviable

career as a professional golfer even by today’s standards.

Although his struggles were glossed over in the “keep calm and

carry on” way of the times, I will remember him as an incredibly

brave survivor and a man of honour who lived up to his word.

Chesterfield 8 Iron stamped for Eddie Anderson c.1947 (Private Collection) |

My grandfather’s spirit lives on

My research led me to find my grandfather but none of this would

have been possible without a chance connection to Leon (Old Golf)

Rowbell, a historian and champion of the early golf professionals

in Australia - so many of whom have died alone and forgotten. He

followed me down the research rabbit hole and provided me with the

old newspaper clippings to help me connect with the grandfather I

never knew.

Finding my grandfather Edward (Eddie) William Anderson and

uncovering his story has been truly bittersweet. I am grieving for

a man I feel like I just lost, even though he has long since

passed.

When I found his war photo, I knew he was my grandfather because

my mum looks just like him. I really wish I knew him, walked the

golf links with him, and heard from his own lips his story of

survival and success. As I look in the mirror, genetic inheritance

tells me I have my grandfather’s cheekbones, his jawline, and his

freckles so at odds with my golden skin. But I like to think I

also inherited Eddie’s grit, his determination, and his will to

survive and beat the odds.

Vidya Anderson with her grandfather’s WWII enlistment photograph (Supplied) |

A Peek at History - Helen's Dance

Tony Hill takes a look at the 1936 Tour of Australia and New Zealand by Gene Sarazen and Helen Hicks.

Gene Sazaren made a good living as a touring professional in North America, but also took the opportunity to top up his earnings by making lucrative overseas Exhibition Tours.

He first visited Australia in 1934 with Joe Kirkwood, spending seven weeks cleaning up against the best Australian professionals could offer, finishing second in the Australian Open to Billy Bolger (when he was short priced favourite to win), and sharing third place in the stroke play section of the VGA Centenary Open in mid-November.

By the time he left in November 1934, it had been reported in the Australian press that Gene Sarazen would tour Australia again, probably sometime in 1936.

|

In addition to being a world-class golfer, Eugenio Saraceni was an experienced and astute businessman. His previous golf exhibition tours - with various partners - had been successful, and he was not beyond a little bit of self-promotion if it meant extra money through the gate. Prior to leaving for the 1936 tour of New Zealand and Australia, he had taken great pains to extol the golfing prowess of Helen Hicks over that of Mildred "Babe" Didrikson, his earlier proposed partner. He suggested repeatedly that she was a much better golfer, and in a letter to Slazenger's Ltd. (the organisers of the tour) went on to say that she was good enough to compete in the Open Championships of the two countries - something that received considerable newspaper coverage. In the Sydney Daily Telegraph of 25th March 1936, it was reported that a Slazenger's executive had confirmed that the New Zealand golf authorities would have no objection to an entry being lodged by Miss Hicks. It went on to say that they had put forward the date of Open to enable her and Sarazen to compete, though perhaps Sarazen was most in their thoughts when this concession was made. The same article also quoted the secretary of the Australian Golf Union as saying that there was no clause excluding women from entering the Australian Open, and - perhaps more interestingly - that he 'could not see any reason why they should not'. |

Sydney Daily

Telegraph

25th March 1936 - p.30 |

Sarazen and Hicks set out from Vancouver on their great adventure in mid July 1936, aboard the SS Mariposa, arriving in New Zealand for a two week ‘stop over’ in early August.

While there, they played eight exhibition matches in 11 days against some of the best Kiwi golfers, both amateur and professional, on some of the best courses New Zealand could offer.

They were far from disgraced, winning three of the competitions, halving two, and losing three. Helen played all her matches off of the men’s tees and used the unfamiliar - but regulation - small (1.62") ball in New Zealand. And she was ‘no mug’ when playing against the boys.

| Date |

Course |

Opponents |

Result |

| 7/8/36 | Maungakiekie Golf Club One Tree Hill, Auckland |

T. S. Galloway Jim Ferrier |

Lost 4 & 3 |

| 8/8/36 | St Andrews Golf Club Hamilton |

T.S. Galloway A. Murray |

Halved |

| 10/8/36 | Arikikakakapa-Rotorua Golf Club Rotorua |

S. E. Carr J. McCormack |

Won 7 & 6 |

| 11/8/36 | Poverty Bay Golf Club Gisborne |

W. D. Baker W. D. Armstrong |

Won 2 up |

| 13/8/36 | Manawatu Golf Club Palmerston North |

J. R. Galloway J. P. Hornabrook |

Lost 1 down |

| 15/8/36 | Hutt Golf Club Lower Hutt |

J. Black B. Silk |

Won 1 up |

| 16/8/36 | Timaru Golf Club Washdyke |

E. G. Kerr Jr. J. K. Mackay |

Lost 4 & 3 |

| 17/8/36 | Christchurch Golf Club Christchurch |

C. J. Ward H. R. Blair |

Halved |

|

Adelaide News

7th August 1936 - p. 1  Daily Telegraph

8th August 1936 - p. 18 |

At around the same time that Sarazen and Hicks arrived in New Zealand, conjecture regarding Helen Hicks' participation in Open events in Australia started to appear in the local press. The front page of the Adelaide News reported that Miss Hicks was going to play in both the S.A. Centenary Open and the Australian Open. It went on to say that her presence would "make the golf one of the biggest centenary attractions, and should assure the S.A. Golf Association of record gates." The following day, the Sydney Daily Telegraph reported that she would not be playing in the Centenary Open because she'd be too late to nominate, but she would still be in time to nominate for the Australian Open. The Australian golfing public were none the wiser, but they were better informed. |

They arrived in Sydney on 22nd August after a very rough crossing of the Tasman Sea and walked straight off the RMS Makura into an Exhibition Match that afternoon against Jim Ferrier and T. S. McKay at the NSW Golf Club, La Perouse.

From there, they played a series of matches progressing up the Australian east coast to southern Queensland, and then back down the same coast to Melbourne, before turning west to Adelaide. On the way, they took on local golfing talent such as Jim Ferrier (Australian Open winner 1938 & 39), Fred Popplewell (Australian Open winner 1925 & 28), Norman von Nida (Australian Open winner 1950, 52 & 53), Arch McArthur, Mick Ryan (Australian Open winner 1932), Mae Corry and Rufus Stewart (Australian Open winner 1927), and won more than they lost

| Date |

Course |

Opponents |

Result |

| 22/8/36 | NSW Golf Club La Perouse NSW |

T. S. McKay J. Ferrier |

Lost 3 & 2 |

| 23/8/36 | Steelworks Golf Club Shortland NSW |

D. O. Alexander Mrs S. G. Pearce |

Won 3 & 2 |

| 24/8/36 | Royal Sydney Golf Club Rose Bay NSW |

H. R. Bettington F. Popplewell |

Lost 4 & 2 |

| 25/8/36 | The Australian Golf Club Rosebery NSW |

J. Ferrier D. Esplin |

Won 1 up |

| 26/8/36 | The Lakes Golf Club Eastlakes NSW |

J. Ferrier Miss E. Parker |

Halved |

| 27/8/36 | Lismore Golf Club Lismore NSW |

J. C. McIntosh N. Craig |

Lost 3 & 2 |

| 28/8/36 | The Brisbane Golf Club Yeerongpilly Qld |

S. Francis A. H. Colledge |

Lost 1 down |

| 29/8/36 | Royal Queensland Golf Club Eagle Farm Qld |

G. Sarazen v. (£50 Challenge) N. Von Nida |

Von Nida won 2 up |

| 29/8/36 | Royal Queensland Golf Club Eagle Farm Qld |

Miss Helen Hicks & Miss J. Beet v. Miss D. Hood & Mrs F. W. Gardiner |

H & B won 3 & 2 |

| 30/8/36 | Gailes Golf Club Wacol Qld |

N. Von Nida A. S. McArthur |

Lost 1 down |

| 1/9/36 | Warwick Golf Club Warwick, Qld |

T. R. Erby Miss A. L. MacDonald |

Won 7 & 5 |

| 2/9/36 | Stanthorpe Golf Club Stanthorpe, Qld |

J. S. Scully A. Christensen |

Won 4 & 3 |

| 3/9/36 | Tamworth Golf Club Tamworth, NSW |

A. Shephard J. Smith |

Won 4 & 2 |

| 4/9/36 | Concord Golf Club Concord, NSW |

W. R. Dobson J. R. Barriskill |

Won 1 up |

| 5/9/36 | Oatlands Golf Club Oatlands, NSW |

T. S. McKay Miss M. Corry |

Won 2 up |

| 6/9/36 | Kingston Heath Golf Club Cheltenham, Vic |

M. R. Ryan J. Ferrier |

Won 1 up |

| 9/9/36 | Kooyonga Golf Club Adelaide SA |

R. Stewart Miss K. Rymill |

Won 4 & 3 |

The South Australia Centenary Open Championship at the Royal Adelaide Golf Club at Seaton was a 72 hole event, played over the three days 10/11/12th September with a ‘cut’ after day two, and 36 holes on the third day.

By the time they had reached the South Australian leg of their tour, Helen Hicks had - despite previously reported impediments to entry - nominated to play in the South Australia Centenary Championship. The Championship Committee didn’t have a problem or an issue with the application, and it was widely reported.

The reporting was almost unanimously enthusiastic, however just a couple of days before the event, a well known - but unnamed - Australian golfing professional had lodged a ‘formal objection’ to having Helen Hicks, a women, entering their tournament. The objection was dismissed out of hand.

As a ‘warm up’ for the Open, both Gene and Helen took part in an exhibition event at Kooyonga, and defeated Rufus Stewart, the local professional and winner of the 1927 Australian Open, and Miss Kathleen Rymill, the current Women’s State Champion. Sarazen and Stewart went out in 37, Hicks took 39. The locals were defeated 4 & 3.

As dawn broke over the RAGC at Seaton on the 11th of September, Gene had turned up to “play” and his travelling companion, Helen Hicks, had a date with history. The organising Committee had played fair and partnered Helen up with two good playing partners - D. C. Turner, the current Royal Adelaide Club Captain in the first round, and, in the second round, T. S. Cheadle, multiple Royal Adelaide club and South Australian state amateur champion.

At the end of the first round, Miss Hicks was far from disgraced and had carded a score of 78, eight shots behind the leader, and level with well-knowns Len Nettlefold, George Naismith, Legh Winser and Bruce Auld. In fact, her first nine score of 38 was better then Sarazen's!

Her second round of 81 was not as good as her first, but her two round total of 159 had her well and truly inside the cut off score of 174. She had qualified for the final 36 holes, but withdrew, citing poor health and feeling 'tired' after what had been - to date - a rather hectic schedule.

Helen Hicks was not an embarrassment - she played with style, credit and belief. She holds the record – the first women to play in a Men’s Open Tournament in Australia on equal terms.

In the years to come, there would be others who would try their luck.

- The Lakes Open. In July 1939 Babe Didrikson shot 77 and 89, and was disqualified during the third round. She was refused entry into the Australian Open the following week. She did receive a formal Invitation to play in the New Zealand National Open in September of that year but was unable to attend. The Second World War had started, and she and her husband needed to return to America.

- The 1953 Ampol. In October 1953 at the Lakes, "The Ampol Four" - Alice Bauer, Jackie Pung, Peggy Kirk and Marlene Bauer played all four days.

And as for Gene Sarazen and Helen Hicks. Gene would go on to win the 1936 Australian Open held at the Metropolitan in Melbourne with a four round total of 282, and they would continue on their ‘walkabout tour’ playing 18 more Exhibition Matches, taking on such a venerable mixed pairs as Jim Ferrier & Mrs Sloan Morpeth, and denting the egos of Ivo Whitton and Ted Naismith at Royal Melbourne.

And continue to meet some very interesting people.

A Peek at History - The 'Forgotten' Golf Ball

Tony Hill takes a look at what could have become the preferred golf ball.

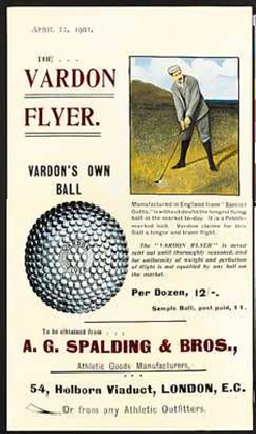

If you get the chance, do go and visit the Australian Golf Heritages Society Museum’s display Having a Ball. It’s both intriguing and enlightening to see the types of golf ball used by our forefathers. It includes a replica of the Vardon Flyer, and a gutta percha golf ball by Spalding in 1899.

Whenever you play the noble game of golf today - no matter the brand - the most common type of legal ball is 1.68” two-piece construction ball, often referred to as the American ‘big’ ball.1 Go back in time a few years and we used a wound three piece golf ball that was covered with either Surlyn or, as preferred by the tournament playing professionals, the softer touch of Balata. And there are just some of us who are old enough to remember learning the game with the small 1.62" ball, also known as the British Ball.

However, for a few years in the early 1970s, there was a third size in golf balls that both the R & A & the U.S.G.A. sanctioned for use by the golfing public - the 1.66” golf ball.

The United States Golf Association (U.S.G.A.) had announced in 1930 that their 1.68" ball was to become “legal tender”, but the bickering between The Royal & Ancient Golf Club (R&A) and the U.S.G.A. would continue for another 45 years. In November 1946, President of the Royal Canadian Golf Association J. A. Fuller announced that Canada would use the American ball from January 1948. The North American market place had gone and the R & A had lost control of the situation. Similarly, the Australian press in the 1950s felt it was only a question of time before we changed to the big ball.

North America pros visiting Australia generally chose to re-learn how to play the small ball. In October 1952, when four American Tour pros (Jim Turnesa, Lloyd Mangrum, Ed ‘Porkie’ Oliver and Jimmy Demaret) visited Australia to play in the 1952 Ampol at the Lakes, it provoked an interesting question before the Tournament began when Demaret was reported as saying they might use the small and large ball alternately – depending on which way the wind was blowing. At this time, there was nothing illegal about using either or both sizes of golf ball outside North America.

In the late 1960’s, The R & A attempted a compromise solution to the issue, offering up two alternatives – a 1.65” and a 1.66” golf ball. Discussion raged. A John Husar July 1969 article in the Chicago Tribune pondered over golf ball sizes, and on February 7th 1971, the Sydney Morning Herald had an article on the drawn out controversy of golf ball sizes that refused to go away. The May 7th 1973 edition of the Milwaukee Sentinel questioned the “reluctance” of the U.S.G.A. to reconsider golf ball size. The R&A conducted extensive testing with the 1.66” ball in Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa. The ball was released for the common golfer to use.

In the end it did not stack up. The top dog in the English and European golf professionals community Tony Jacklin used the big ball to win the Jacksonville Open Invitational in 1968, the 1970 San Diego Open, hustled the locals on their home turf at the 1970 U.S. Open (winning by 7 shots), and returned to win the Greater Jacksonville Open again in 1972.

In 1974, with the fear of American anti-trust laws breathing down their backs, The R & A made the 1.68” golf ball compulsory for the British Open. The writing was on the wall and the 1.68" ball gradually took over. The buying public didn’t want to use yesterday’s material and the 1.62” golf ball was formally outlawed in 1990 by The R & A.

And as for the 1.66” golf ball – it never advanced past the testing stage, and disappeared into history.

You can read a little more in the article 'One Size Didn't Always Fit All' on the U.S.G.A.'s website.

1. In June 2019, Callaway released the 1.732" Supersoft Magna as a game improvement gadget which "subtly raises the center of gravity of the ball and makes it easier for less-skilled players to get the leading edge of an iron or wedge under the equator of the ball to make solid contact."

- Tony Hill

Book Review - Open Fever

Dr Frazer's Australian Open Golf Championship by Colin Strachan

Reviewed by Vicki Stanton

In this handsome and

well-presented hardback book, Colin Strachan has meticulously

researched not only the life and achievements of Dr Ewan Frazer,

and in particular his legacy to medicine and golf, but places

Frazer and his family in the social context of the time. Strachan

traces the emigration of the impoverished Frazers from their

native Ireland to Sydney and how through entrepreneurial ventures

rise in wealth and social status.

In this handsome and

well-presented hardback book, Colin Strachan has meticulously

researched not only the life and achievements of Dr Ewan Frazer,

and in particular his legacy to medicine and golf, but places

Frazer and his family in the social context of the time. Strachan

traces the emigration of the impoverished Frazers from their

native Ireland to Sydney and how through entrepreneurial ventures

rise in wealth and social status.

Strachan then narrows his focus to Ewan Frazer. He traces Frazer’s time as a medical student at Oxford University, his involvement with Royal Ashdown Forest and Tunbridge Wells Golf Club, his marriage and the death of his brother Arthur. The lens then pans out to a discussion on early golf in New South Wales; the formation and development of The Australian Golf Club, its people and its courses; and the founding of the Australian Golf Union and the Suburban & Country Golf Association of NSW.

Chapters 13 and 14 get into the real meat of the book. Ewan Frazer becomes secretary of The AGC and Strachan details the personal and financial commitment of Frazer to secure and construct the Kensington links and works tirelessly to extend the Botany course to play the first Australian Open. The book winds up with more on the life and pursuits of Ewan Frazer and his family.

Strachan writes with detail yet I never felt overwhelmed by information which is complemented by copious images selected from a wide range of sources illustrate the social, familial and sporting world of Frazer. This is a necessary story that is well told by Strachan. Frazer’s legacy is not only in the establishment of golf in the early twentieth century in Australia, including women’s golf, but also in his largesse to Oxford University’s pathology department without which the work on the development of penicillin could not have proceeded. For those wishing to follow up, there is a very helpful index, list of references and sources at the end of the book. The endpapers also feature a helpful family tree.

HB $50 plus postage (available from The Australian Golf Club)

ISBN: 9780646994703

Colin Strachan on Dr Ewan Frazer – Pioneer in Australian Golf

This talk by British golf historian, Dr Colin Strachan, was organised jointly by AGHS and the Australian Golf Club. It took place on the evening of Monday 27th February at the Australian Golf Club. Seventy one people attended.

|

| AGHS golf historian Michael Sheret introduces Colin (click for larger image). |

Colin held the attention of his audience admirably with a well-researched interesting topic and an excellent PowerPoint presentation. The Frazer family is an interesting one, from rags to riches in Australia in the 19th century. Ewan Frazer was the Honorary Secretary of the Australian Golf Club. Over the period 1903 to 1905 he was the driving force in securing the land at Kensington for the Club’s present course, often putting his own money on the line for the land and the construction of the course and clubhouse.

|

| Colin Strachan and some of his audience (click for larger image). |

He was also the driving force in getting the first Australian Open up and running in 1904 and holding it at The Australian Golf Club at their Botany links. On his return to England both he and other members of the Frazer family were prominent in the development of Royal Ashdown Forest, Colin’s home golf club. A man of many parts, Ewan Frazer was also a pathologist and played a significant part in the development of the Department of Pathology at Oxford University.

The whole evening was a great success. Champagne on arrival, a riveting talk, a rapt audience, a gourmet dinner with unlimited wine, excellent service and a convivial atmosphere. All this in the beautiful setting of one of Australia’s most prestigious golf clubs. AGHS members interested in golf heritage and having an enjoyable evening at a bargain price, and didn't attend, missed out badly.

|

| AGHS President John Buckley giving the vote of thanks. |

A special thanks goes to Don Dunne, a member of both the Australian Golf Club and the Australian Golf Heritage Society, for his tireless work in publicising this event and making it a success.

- Michael Sheret

Perry Somers - Ten Questions

Many AGHS members would be familiar with the name Perry Somers. A member of both the Australian and German PGA, Perry's hickory honours include being a twice winner of the Australian Hickory Shaft Championship (2009, 2010), winner of the World Hickory Open in 2010, twice victor at the L’Open de France (2009, 2012), winner of the International Dutch Hickory Open in 2016, and numerous 'podium' finishes.

|

| Perry Somers - 2010 Australian Hickory Shaft Champion |

Now based in Cologne, Germany, Perry was recently interviewed by

North-West Hickory Players (U.S.) co-founder Robert Birman as the

lead-off subject of a new series of interviews with avid hickory

players.

The ten questions asked by Robert, and the replies follow:

1. The back-story - A diminishing number of

passionate hickory golfers today know the names of the few-dozen

men and women who championed the rebirth of the interest in this

game. It is fascinating to me that the development and momentum of

this interest has been steady across the globe in the last 10-15

years. What was your path, and who - if anyone - inspired you to

get started in this niche of the game years ago?

Answer: Initially, there were no inspirational

figures. I simply had a fairly superficial interest in the history

of the game. I was member of the Golf Society of Australia who had

organised a nine hole hickory outing on the fabulous Kingston

Heath course in Melbourne. After just two holes I knew I had found

what I had been missing in recent times from the game. Since

joining the British Golf Collectors Society I have been inspired

by Iain Forrester and the inimitable President Philip Truett.

2. The hardware - You've earned more than your fair

share of trophies and awards in the hickory golf community

globally - congratulations. You comport yourself with class and

professionalism and are one of few truly global ambassadors for

the game. First, what do you do with all of that hardware, and

second, if you could only keep one item, which would it be and

why?

Answer: I’d like to know what ones “fair share”

would be actually. I don’t have many trophies at home, as most are

of a perpetual nature. I have been fortunate enough to win some

lovely medals over the years that have been beautifully inscribed

with relevant motives. Forced to choose, which I would not enjoy

doing, I would probably choose the first medal I ever won, which

was the 2009 French Hickory championship. By the way this was my

first, of many, head to head battles with Randy Jensen, as it was

a handsome medal embossed with the scene of the opening day of the

Chantilly G.C. in 1909.

3. The gear - Few hickory players travel and

compete as much as you do. How many clubs go with you on a typical

trip? Can you tell us about your favorite play clubs and comment

on considerations you make in adding or subtracting clubs based on

specific events?

Answer: Your readers are bound to be disappointed

with my lack of information as I am well aware of the amount

interest in the technical aspects around the US hickory scene. I

carry seven clubs for parkland golf, ( Brassie, Baffy, Cleek, Mid

Iron, Mashie, Mashie Niblick and Putter) a complete fruit salad of

brands and makers, and two more for links golf. ( A Driver for a

more penetrative flight in the wind and a Niblick for the Pot

Bunkers. ) Favourite: possibly the Mashie Niblick.

4. The ladies - Social media allows us all to see

the growing number of players who turn out for big and small

events around the globe. I know you're a student of golf history

and you (like me) admire Joyce Wethered, among other historical

figures. How often, today, do you get to play rounds with female

hickory golfers and what are your general observations about the

growth of the women's game in our sport?

Answer: You are absolutely correct in your

assumption to my Joyce Wethered allegiance. I am also considerably

jealous of her life in general. On and off the course she led a

charmed existence. Starting with a childhood full of summer

holidays in Dornoch to the incredible success in tournament golf,

playing matches in the US with the immortal Bobby in the “hard

times” of the depression through to marrying into substantial

wealth and becoming Lady Heathcoat- Amory! As to the ladies scene

here in Europe, I can report a continued increase in female

participation from event to event. The queen of the European

Hickory scene is my friend Britta Nord from Sweden with whom I

have been fortunate to play many times.

5. The competition - Match play and stroke

competitions, in hickory golf, almost always combine an equal

measure of affection and determined competition. Every player

wants to win, but most would never trade that for the warmth and

spirit of friendship that stems from our community of players. I

have found that my favourite match was one that I was virtually

certain not to win, and I didn't, but I enjoyed that round more

than any other I can remember. Without naming names, unless you

care to, can you reflect on a favourite match in your memory and

what made it so memorable?

Answer: I couldn’t agree more. The matches we play

in early June on the Norfolk Coast against Royal West Norfolk and

Hunstanton G.C. respectively, for example, are the most pleasant

golf days I have ever enjoyed. No pencil & card golf! Just

foursomes followed by a convivial lunch.

6. The travel - Few have logged the miles you have

in this sport. Are there any simple principles you can share about

making hickory golf trips, and the act of packing, fairly

efficient? We golfers often have to plan for inclement weather.

How do you handle your own preparation, in terms of clubs, apparel

and luggage?

Answer: Given the disgusting way baggage handlers

around the world handle our luggage, I take the extra precaution

of packing all my clubs inside a PVC tube that is superb

protection for the shafts. See photo below. I make no extra plans

for inclement weather. I play in a tweed jacket and that was good

enough for Braid, Vardon, Taylor and Co. So I have to do the best

I can in the conditions with the relevant clothing.

|

| Perry's PVC Tube Club Carrier (click to enlarge) |

7. The collection - I'm curious if there is any one

club, ball, medal, or golf collectors' item you would choose, if

you could find anything in all of golf history (and someone else

would pay for it!) What might that be, and as important, what

would you wish to have done with it once you are gone?

Answer: This is where I “out” myself as non hardline

collector. I wouldn’t have a club or medal as such, however I

dream of playing St. Andrews or any traditional links course with

a traditional set of long nose play clubs and the feathery ball.

That would be very special!

8. The off season - With your travel schedule, you

may not have a clear cut off season, but my question is about care

and maintenance of your play set. Do you have annual routines you

follow to keep your clubs in peak playing condition?

Answer: I do indeed have an off season and by the

way, I am no longer as active as previously. I do give my

hickories a winter reconditioning. Generally a light sanding down

and a light coat of shellac.

9. The shot-making - I think most golfers have a

shot or two that we enjoy re-living in our memory when we reflect

on our time on the links. Can you share one of yours - what

course, which hole, what shot did you pull off?

Answer: One that springs to mind was in the

re-enactment of the “1870 Great Match” against Randy Jensen. We

had played for three days on three different courses St. Andrews,

Prestwick and North Berwick and I was one up on Musselburgh’s 15th

hole. The hole was a par four with a very difficult two tiered

“table top” green. I had driven in the light whispy rough and

suspected a “flyer” from the lie. I lay no more than one hundred

and forty yards from the hole which was cut up on top of the

table. There was no chance of stopping anything played high ( a

modern shot) so I played what used to referred to in the hickory

era, as a “push shot”. Basically a pitch shot with the mid iron

out of my hands and arms only, that flew on a low trajectory,

pitched in front of the green and scampered up the steep tier to

settle eighteen inches behind the cup. The birdie set me two up

and another followed on the par five seventeenth which brought the

match to it’s conclusion.

10. The future - As someone who meets players all

over the world, what's your prognosis for the future of hickory

golf?

Answer: I most certainly do not have a crystal ball,

however, I am very concerned at the lack of interest in the true

traditions and the lack of effort to re-create the atmosphere of

the early 1900s. Far too many corners are being cut and

compromises too readily sought. Too many people using carts and

trollies, too many wearing modern clothing, particularly in poor

weather and far too many playing non traditional equipment. There

will most certainly come a time when all the original hickory

clubs have been purchased, used and broken, but that is thankfully

not currently the case.

This article appears courtesy of the North

West Hickory Players and Mr.

Perry Somers. The Australian Golf Heritage Society would

like to thank them for their generosity.

Retrofitting Hickory Shafts

NOTE:

Subsequent to this article being written, the Australian Golf

Heritage Society has decided to follow the lead of the U.S.

based Society of Hickory Golfers, and allow wooden headed clubs

retrofitted with hickory shafts to be used in AGHS sactioned

competitions. Refer to the updated ‘Golf

Equipment Standard for Hickory Events’

The published aims of the Australian Golf Heritage Society are to:

- Encourage the collection, recording and preservation of information that is connected to the history of golf in Australia,

- Verify the authenticity of physical items associated with the history of golf in Australia and provide a means of storing, restoring and displaying these physical items,

- Inform golfers, golf clubs and the wider community of this information and display these physical items in a manner which tells their story, and

- Promote hickory events as a celebration of the origins of the game.

In the past the Society and its members have managed to adhere to

these guidelines reasonably well, but as interest in the history

of the game increases, we find that these aims can sometimes come

into conflict, particularly where hickory events are involved.

We have published - in our current ‘Golf

Equipment Standard for Hickory Events’ - the following as

our approved standard for wooden headed clubs:

Wooden Headed Golf Clubs, with

plain wooden shafts:

- Must have Heads manufactured before 1940.

- Shafts may be repaired or replaced with an old or new shaft.

- Must have a ‘leather wrap’ grip.

- Weight may be added to the head.

Further to this, we say by way of ‘Explanatory

Notes’:

It is understood that old golf

clubs manufactured prior to 1940, may not be in very good

condition and need different levels of repair and maintenance.

The above guidelines make it

possible for the owner of these clubs to do his/her own repairs

and maintenance, if he/she wishes to do so, without further

expenditure.

Generally, any repair or

renovation that would have been performed prior to 1940 is

acceptable.

All enquires are welcome and

should be directed to The Secretary, Golf Society of Australia

Inc. or Australian Golf Heritage Society.

The supply of Australia specific clubs is – quite obviously –

finite, and this is particularly true of the wooden headed clubs.

As a relatively small market with a correspondingly small number

of local club makers, it is also equally obvious – and

counter-productive – to be using increasingly rare and

increasingly valuable Australian clubs in play events.

It is indeed possible to buy clubs from the much larger United

Kingdom and United States markets, but by the time that you have

tracked down what you think are suitable clubs, purchased them

sight unseen, and had them freighted down under, the cost is

somewhere between prohibitive and extortionate . . . and there’s

still no guarantee that they will be playable. But there is a

ready solution at hand.

On the other side of the Pacific, the Society of Hickory

Golfers (SoHG) have recognised that a similar problem

exists. They have arrived at a more comprehensive set of rules

which caters for their much wider playing base. Included in the

Rules is the following clause:

RETROFITTED CLUBS. – This

category was created for clubs that were made PRIOR to Dec. 31,

1934. Any wood headed club offered for sale prior to 1935,

regardless of shaft material originally installed at time of

manufacture may be retrofitted with a wooden shaft and be

permitted for play in SoHG sanctioned events.

Players must establish – independently or through the

retrofitter or seller of these clubs – that the heads were

indeed offered before 1935. No golf club made after Jan. 1, 1935

will be allowed in this category. It should be noted that no

irons (iron headed clubs) have been approved to be retrofitted

with a wood shaft for play.

Some time ago, Brisbane based AGHS member Ross Haslam took the

SoHG supplementary rule on board, with the dual ideas of creating

a hickory environment where the preserving of the precious local

artefacts was possible, and obtaining a decent set of woods wasn’t

a one-way ticket to the poorhouse.

Ross purchases his ‘raw material’ from the United States, and he

chooses pre-1935 rather than pre-1940 (as per AGHS hickory playing

guidelines) as it is generally much easier to identify a pre-1935

wood compared to a pre-1940 version. Up until circa 1935 large

American club manufacturers such as Wilson and Macgregor were

offering hickory shafts as an option in many club styles, even

though they had long committed to producing and promoting steel

shafted clubs.

By the late-1930's manufacturers were often using numbers (1, 2,

3) and/or traditional names on wood clubs, and the use of the

"Phillips head" screws in face inserts and base plates was

increasing. They were also experimenting much more with club head

design compared to the first half of the 1930's. As a consequence

it can be very difficult to differentiate between a pre or post

1940 steel shafted wood club.

All of the wood clubs Ross has chosen to re-shaft are very easy to

identify as pre-1935 via catalogues and many are sold in both

original hickory or steel shafted versions online. Ross has done

the AGHS a considerable service by documenting his retro-fitting

process and choosing – unselfishly – to pass his expertise on to a

wider audience. Over to you, Ross . . .

How I re-shaft a pre-1935 steel shafted wood with a new hickory shaft

Once you have your pre-1935 wood the first, and usually the most difficult step, in the entire process is to carefully remove the steel shaft without causing too much damage to the wood head.

A circa 1935 steel

shafted Leo Diegel “Banner” Wilson driver

|

The steel shaft of most pre-1935 steel shafted clubs was held in

with 2 screws. The first is usually a longer screw, approximately

30mm long, running perpendicular to the hosel of the club and

passing through the shaft to secure it into the clubhead. The

second is a shorter screw approx 15mm long that skews back into

the clubhead through the shaft where it penetrates through the

base of the club.

On occasion you may find this screw is actually a pin that has

been nailed through the shaft (these are difficult to get out).

The other variation you may see, particularly in latter clubs, is

that the screw through the hosel may have a very small head

(making it very hard to extract) or may not have been used at all.

A steel shafted wood

showing the 2 places where the shaft is usually screwed

|

The shaft removed

showing the 2 fixing points

|

A pre-1940 Spalding

Kro-Flite 2 wood with no hosel screw

|

Removing screws that have been in place for 80+ years can be a

trying experience. They are nearly always slotted screws that are

filled with dirt and other gunk and are often worn away leaving

little slot for a screwdriver to fit into. A pair of loupes is

essential for examining the condition of the slot and determining

the angle that it is screwed into the club.

I use a Stanley knife blade to clean the slot as thoroughly as

possible and make sure that I have a screwdriver that fits the

slot snugly. You need to ensure the shaft of the screwdriver runs

parallel with the angle that the screw has been inserted into the

club and that pressure is exerted directly down the shaft, you

only get one go to get these screws out. If not the blade can

twist out of the slot and damage it to a point where you will be

unable to apply any pressure to remove the screw.

If they refuse to budge (and they often do) I drill them out from

the base with a bit that just fits into the hollow centre of the

shaft. After drilling up through the shaft the head of the hosel

screw usually sticks up enough to grab with a pair of pincers or

fine pliers. Remember that the end of both screws will both need

to be punched into the clubhead to clear the inner wall of the

steel shaft. Once they have been punched clear the shaft should

turn freely and can be pulled out. If the shaft doesn’t turn

freely chances are one or both of the screws will not have been

punched clear of the shaft.

The remaining clubhead can now be trimmed and bored out ready for

fitting of the new hickory shaft. I cut the hosel at the point

where the width of the hosel will match the diameter of the new

hickory shaft. Because the hosel of a steel shafted wood is

narrower where it meets the steel shaft you will need to cut the

hosel closer to the clubhead than you would for a normal hickory

shafted club. This in turn means that the whipping will run closer

to the top of the clubhead than a normal hickory shafted club.

The angle of the hosel is much greater in a steel shafted wood |

I bore out the hosel using a step-drill that steps from 4mm to

12mm in 9 graduations. I use the “CraftRight” brand from Bunnings

which come in a set of 3. There are more expensive single bits

that have 12 graduations but I find the Bunnings bits are fine. I

have lengthened my bit by adding a hex bit from a socket set. This

allows me to drill through the hosel with plenty of clearance. I

drill the hosel by hand using a cordless drill with the clubhead

secured in a vice.

I generally drill through the base until the 4-6mm graduation

appears, from my experience this gives a hole in the base of a

similar size to what is normally seen in hickory clubs. With the

hole from the steel shaft already running through to the base of

the club it is just a matter of using this as a guide and slowly

advancing the step bit. You may shave a bit off the base plate,

depending where the steel shaft exited the base, but being

aluminium or brass the step bit handles this easily and will leave

a neat oval shape (see the Kro-Flite above).

4 to 12mm step drill

bit attached to hex bit

|

Examples of some

clubheads trimmed and bored out ready for re-shafting

Fitting the new hickory shaft is now simply a matter of carefully

filing down the end of the shaft until it is a reasonably snug fit

into the new bored-out hosel. I have a selection of files and

rasps that I use for this. Once I’m happy with the fit I set it in

place with “Ultra Clear” Araldite (you can use whatever glue you

prefer). The important thing at this point is to ensure the grain

of the shaft runs perpendicular to the face of the club.

I mark the grain on the butt end of all my shafts so that aligning the shaft is no problem.

Re-shafted wood

showing new hickory shaft protruding from the base

Now that the shaft is set into place all that remains is the

finishing of the club. To ensure a seamless transition where the

hosel and shaft meet I use epoxy putty carefully sanded back. It

is a time consuming process but if done well the taper from

clubhead to shaft is as indistinguishable as it is in all hickory

shafted woods. The nice thing about epoxy putty is that it will

take stain so you can colour it to match the club head or shaft if

you desire.

Re-shafted woods

showing the epoxy putty prior to finishing

|

It can sometimes take

2 or 3 goes to get the join seamless from every angle

|

Epoxy putty join

finished and stained

|

The finished join with

whipping applied

|

The screw hole at the back of the hosel can sometimes be the only

giveaway that a once steel shafted wood has been re-shafted with a

hickory shaft. After experimenting with casting resin to repair a

damaged face insert I decided that resin would be the ideal

material to fill the hole left by the hosel screw. I place the

club in the vice making sure the hosel area is level. The casting

resin I use takes 5-10 minutes to set so when ready I line the

hole with 5 minute Araldite and then carefully syringe in the

resin to just overfill the hole. When set it can be filed or

sanded down to the desired finish. I have begun stamping my resin

plugs with the letter that represents the wood, so “B” for Brassie

and so on. If the club has an insert face I try to match the plug

colour to the colour of the insert.

Slightly overfilled

resin plug in hole left by hosel screw

|

Green resin plug

finished and stamped with “B” for Brassie

|

As a lefty it is difficult to come across decent playable hickory shafted woods. In championship play I use an original hickory shafted Alex Patrick Brassie from the tee and a Spalding 2 wood (with a repaired insert face) from the fairway. I've yet to find a playable original hickory shafted spoon for use in championship play. In social play I use a re-shafted 1935 Walter Hagen "Tom-Boy" spoon.

My 1935 Wilson "Walter Hagen Tom-Boy" re-shafted spoon

Early Golfers in Ireland, America, India and Australia

From

the earliest days, military golfers have had a significant role

in spreading the game of golf outside the British Isles. The

mariners and civil servants of the British Empire also played

their part in popularising the game in far foreign fields.

Bill with the Distinguished Service Award

from Irish Golf Writers, 2011

|

On Thursday 28th April 2016, starting at 5

pm there will be an illustrated talk at the AGHS Museum

by visiting golf historian, Colonel William Gibson. Bill is a retired army officer. He has

extensively researched the history of his own club,

Royal Curragh Golf Club in County Kildare. His research provided the evidence that

Royal Curragh had its beginnings as far back as 1852,

with military personnel posted to the area. Bill was made an honorary life member of Royal Curragh in 2009. He has also researched and published the definitive work on the very earliest golf known to have been played in Ireland, dating back to the early 17th century.

|

If you intend coming to the talk, contact the History Sub-Committee via the Contacts page. Alternatively, telephone the AGHS Museum, 10am to 4pm Sundays on 02 9637 4720 at 4 Parramatta Road,(above Golf Mart), Granville 2142.

Peter Corsar Anderson - A Developer of

Golf in Australia.

Barry Leithhead's collation of information on Anderson’s contribution to the history of Australian golf.

GOLF IN AUSTRALIA was founded by people from ‘the old country’ who brought it here, with ancient implements and the desire to find suitable ground on which to play. That foundation was developed by others who followed – men like Peter Corsar Anderson.

Peter Anderson had two passions in his long life –

education and golf. He was already an accomplished Scot when at

age 25 he arrived in Australia in 1896, having graduated from

the old St Andrews University with MA and post-graduate studies

in Divinity. Anderson had also graduated from the Old Course at

St

Andrews, where he played often and well, holding for half a

season the course record of 80, which was four under bogey. His

golf was so good that in 1893 when only 22, he won the British

Amateur Championship at Prestwick, beating JE Laidlay in the

final. However, he was in poor health with pleurisy and hoped

for a better climate in Australia. Arriving in Albany, then the

major port in Western Australia, he met his elder brother Mark

who was a shipping agent there and also a fine golfer.

Albany is some 360kms south from Perth, where the Antarctic wind first assaults the golf course. Mark suggested Peter settle in Melbourne, where he had been Champion of the Melbourne Golf Club in 1893. Peter did not delay and within a short time had taken up a tutoring position with a well-to-do farming family at Mansfield, 90kms north east of Melbourne. Six months later he was appointed a master at Geelong Grammar School (GGS) and became a member of Geelong Golf Club (GGC).

If his golfing results are an indicator, Peter regained his health quickly. Within a year he had set the course record of 79 for GGC and he reduced it to 76 in 1898 and 75 in 1899, a record that stood until 1904 when his brother Mark reduced it by a single stroke. Peter won the first Championship held at GGC in 1898 and was Champion for six successive years until 19031. Not surprisingly, Geelong won the Victorian State Pennants Championship from 1899-1901 and tied with Royal Melbourne GC in 1902. It is reported that in 1904 Peter Anderson won a pennant match 16 up! The Riversdale Cup was an important event and he won that in 1898-9 and 1902. Mark had won that Cup in 1896, its first year.

Consider the clubs Peter played with, bought from Tom Morris, paying 2/- for a head and 1/6 for a hickory shaft from America. His most expensive club was a brassie which cost 5/6. He won the Amateur Championship of 1893 at Prestwick with six clubs: a brassie, a mid-iron, a cleek (for long approaches), a mashie, a niblick, and a wooden putter he also used for the short game. As a reserve, he had a driver, which he did not use. At Geelong GC is it said he used only four clubs; driver, cleek, mashie and putter and rarely carried a bag for his clubs.

- PC Anderson was reported to be one of those who selected the new site for the Royal Melbourne Course when that club’s old links were becoming hemmed in by building projects2. He is also credited with laying out the Barwon Heads course at Geelong although the course did not open until 1907, well after he had gone to Perth.3

A Geelong Grammar student recalls:

PC Anderson (‘Andie’) joined the school direct from a world golf championship at St Andrews4 and was naturally an idol in the eyes of the sports loving community. His very broad northern accent captivated us and he joined the boys (chiefly juniors) on their excursions into the bush then surrounding parts of Geelong. Knowing nothing whatever of Australia and its bush life, he welcomed these days and in them learned something of the conditions of his adopted country.5

The GGS Quarterly reports:

Mr Anderson has taken his golf clubs down to the river on several occasions, and has kindly given some of the fellows some hints on how to use them, in the race-course paddock. One of the fellows did not seem to be very enamoured of the game, describing it as ‘the most dangerous thing since Waterloo’. He, of course, spoke from sad experience.6

PC Anderson developed substantially as an educator in Geelong. He was a Master at the GGS senior school from 1896-99 and in charge of the Preparatory School from 1899-1900. In 1899 Anderson married Agnes Henrietta Macartney, the sister of the student he tutored at Mansfield and granddaughter of the Anglican Dean of Melbourne who in 1855 was one of the founders of Geelong Grammar School. Peter and Agnes became parents to six sons and seven daughters. He left GGS in 1900 to set up his own school, St Salvator’s, also in Geelong.7

Peter might not have contested the 1904 Geelong GC championship, having moved to Perth, and it was won by his brother Mark – the first of his three championships at Geelong (also 1907 and 1912). He was made a life member of GGC in 1917. Mark also won the Royal Melbourne Championship five times, the first time in 1893 (Easter – the event was played twice a year in 1893 and 1894) and then in 1894 (twice), 1895 and 18968. There’s a nice quote in the RMGC history from RAA Balfour-Melville, who won an Australian Amateur title but could never beat him in a club event – ML Anderson always seemed to sink a long putt on the 18th!! Mark was runner-up in the 1905 Australian Amateur Championship at Royal Melbourne. In the twelve years between 1903 and 1914, Royal Melbourne won the State Pennant Championship nine times.

In 1904, PC Anderson became Headmaster at Scotch College Perth, Western Australia, where the first four years must have been an all-absorbing challenge for Anderson, the educator. He was intent on developing the learning of students despite the school’s being in such a bad state on his arrival that the governors were thinking of closing it down9.

The school was sited in grossly inadequate temporary premises and was moved to a new site at Swanbourne, seven miles (10 km) west of Perth, where a benefactor offered land. Anderson at once insisted that, unlike his predecessor, he should participate in council meetings, and soon proved himself a vigorous organizer capable of ensuring the success of the move.10

Anderson brought to Scotch College a model of ‘godliness

and manliness’, for he was a ‘typical product of a Scottish

Presbyterian background’, tall at 6’4’’, a strong disciplinarian

whose main interest was in sport, and, although not an

educational innovator, he was a ‘reliable’ leader. The notion of

‘godliness and manliness’ is at the heart of late

nineteenth-century ‘muscular Christianity’, a term coined in

response to the work of Charles Kingsley, associated with

magazines like the Boys’ Own Paper and a host of popular books

like Tom Brown’s Schooldays and Coral Island, and in recent

years portrayed in films like Chariots of Fire.11

In 1908 we hear a mention of Anderson in relation to golf and then it is where no course or club exists. Scotch College is within sound of the ocean and Anderson and others thought vacant land on the water’s edge might be the making of a golf course:

Westward towards the coastal sand dunes, a rough gravel track struggled up the hill from Cottesloe Railway Station and lost itself in the scrub at Broome Street. It was early June 1908, and the group of men who trudged up the naturally vegetated hill, battled against a driving westerly wind to the coastline. Among them were FD North, one of the earliest residents of Cottesloe, J M Drummond, T Robertson and PC Anderson of Scotch College. Their common interests were a desire to play golf and to construct their own links. One, Anderson, thought wistfully of his native Scottish links, of his succession of triumphs that had carried him to the very pinnacle of golf as British Amateur Champion. What a contrast between Scotland and this almost inhospitable Australian coastline. Yet, beneath the drab scrub and sandhills of Cottesloe, Anderson could see the possibilities of first-class greens, tees and fairways. It was worth a try. A few nights later, on the 11th of June 1908, before a log fire in the local Albion Hotel Commercial Room, sixteen men met and agreed to form the Cottesloe Golf Club12 13.

This was the origin of the Cottesloe Golf Club in 1908 and Anderson, along with NC Fowlie designed the course aptly named and still known as ‘Sea View’. The opening of the nine-hole course by the State Governor on 11th September 1909 was only fifteen months after the initial committee meeting. A year or so before, Anderson laid out the first nine holes of the Royal Fremantle course, a few miles south from Perth.

In the first two years Anderson won major events at the Sea View course, was appointed Captain in 1912 and one of the Club’s delegates to the Western Australian Golf Association in 1913. Fowlie set the initial course record, bettered by Anderson in 1913 (77) and again in 1914 (75). Fowlie was State Amateur Champion in 1914. Anderson won the Club Championship twice (1917, 1919) when his handicap was +4 and his age almost 50.

It is recounted that two Scotch College students, RD

Forbes and KA Barker were invited by their illustrious

headmaster to play a round of golf with him. Feeling very

pleased with themselves after the completion of their game, one

of the students on returning to the Clubhouse said ‘Sir, would

you care for a drink?’ Anderson said, ‘Yes young man, I should

like a sherry thank you’, whereupon the student dug deep into

his pocket and produced a ten-shilling note which

he laid on the counter. The change however, was picked up and

pocketed by Anderson, a costly but subtle reprimand for the

young players. Forbes would later win the Club Championship ten

times between 1921 and 193814.

Another story told of PC Anderson arose from the activities of a few boys from Scotch who developed a practice of trespassing on the course on Saturday mornings. When the chairman of Greens Committee asked ‘the Boss’ to exercise more control over his pupils, he received the reply: ‘I look after the little beggars five days a week – someone else can worry about them in the weekend’.

PC Anderson won the last of his four Club trophy events in 1928 at the age of 57. He was a committee member from the Club’s founding in 1908 until 1918 – in 1915 he was appointed Vice President, a position he held for 40 years until his death in 1955. He was appointed the Club’s first life member in 193615. Cottesloe GC opened a new course at Swanbourne in 1931, near Scotch College, on seaside dunes/links land with few trees, five kilometres from Sea View. Anderson appears to have played no official part in the move, although the CGC History records that he ‘continued to make a valuable contribution to the establishment of the present course’. His name does not appear in any of the records of the committee who created that course. Perhaps the designers Rees and Stevenson consulted him informally, perhaps even regularly. Given their inexperience in golf course design, it would seem feasible for them to consult the club’s ’grand old man‘ who had designed a number of well known courses. However, the original CGC Swanbourne course would appear to have been largely or even solely the creation of WA Rees and TD Stevenson.16

There was evident dissatisfaction with this original design because the club engaged Alex Russell only a few years later (1934), to redesign the course completely. Russell’s routing, totally different from the original, embodied the then traditional single loop of eighteen holes – nine holes out and nine holes back, like so many famous courses, such as St Andrews. This Russell routing has largely survived today and surely it would have been more to Anderson’s liking. The Sea View course is still in play, bare of trees, on ground that slopes down to the sea.

PC Anderson’s brother, Mark returned to Albany, Western Australia, around 1913. He stayed there, apparently, for the remainder of his life, was Albany Golf Club President in 1922-23 and father of Bill and Jean who were dominant Albany golfers and golf club administrators of the next generation. It is not known from club records whether Mark won any Albany Club Championships (which would seem likely) but he quite obviously became the ’grand old man‘ of the Albany GC. Presumably the Anderson brotherhood started the long close relationship between the Albany and Cottesloe golf clubs which, if not as strong today as once it was, still involves annual club visits.

The extension of Albany GC from nine to eighteen holes (planned in the ‘30s but executed in the ‘50s), was apparently designed by another Cottesloe Anderson – David, CGC’s professional in the 1920s. The Albany GC history records that Mark was an eccentric soul who preferred to putt with a five iron. Tim Catling also tells the following story about his father, Tom, who played with Mark Anderson, when Tom was about fifteen:

Old Mr Anderson was a dour Scot, like my father’s father, given to playing golf in silence. Mr Anderson had two remarkable shots from very difficult lies, and each time Dad asked him how he did it and each time Mark explained, and apart from that did not speak at all. At the end of the round Dad thanked Mr Anderson very much and the reply was ‘that’s all right, you’re a nice lad but you talk too much!’ .

After WWI, PC Anderson seems to have been largely absent from the formal CGC administration. However, he continued to play regularly and was a delegate to the WAGA. It is likely that his perpetual vice-presidency was a largely ceremonial father figure role, a continuation of the ’grand old man‘, the legendary British Amateur Champion of long ago. As such, he gave the CGC a much increased status and aura of credibility. Club members really looked up to him with awe and respect as a figure of considerable stature. Of course, this was assisted by so many of his Scotch College pupils and masters becoming members of the club. There is a huge Scotch old boy contribution to the club to this day. CGC’s History 1893-1983 was compiled by Geoff Newman, a Scotch pupil who later taught under PC Anderson and eventually became the school’s Deputy Headmaster.

Anderson was headmaster of Scotch for 41 years, retiring

in 1945. During this period annual enrolments rose from 59 to

410; more than 3,000 boys passed through Scotch in his time. The

first decade of his regime was marked by the provision of

science laboratories, a cadet corps, sports grounds and a

boatshed. By 1914 Scotch was established as one of the four

leading independent boys’ schools in Western Australia, and for

the next 30 years Anderson was doyen among the Protestant

headmasters, setting an educational model whose influence

extended well beyond his own college. He was a masterful

administrator, careful in times of financial stringency but

insistent on bold planning whenever opportunity permitted.

Impressively built and inclined to be set in his opinions, he

earned the nickname ‘Boss’, but was respected for his scrupulous

fair-mindedness and capacity for hard work. Legends generated

around him, such as the yarn that he once caned the

entire school in an attempt to put down smoking. He was awarded

the CBE in 194717.

Peter Anderson’s great passions for education and golf were played out in three distant arenas – St Andrews in Scotland, and Geelong and Perth in east- and west Australia. Not only was Peter Anderson’s passion for each at a high level but his persistence and determination through difficult times of world wars and the Great Depression were a significant testimony to his character, as was the quality of his golf. The history of golf in Australia is both how the golf was transplanted to Australia and the development of golf once there. Peter Anderson stands tall in both these dimensions of our history. The heritage of golf he brought to Australia, in how he played the game, the clubs he used and his understanding of the game and the course on which it is played, came from the foundation of golf, at the Old Course, St Andrews. When we think of people like Peter Corsar Anderson, we recognise and respect the people who were the founders and developers of golf in this country, on whose shoulders were the burdens of building courses and clubs and the standards of play, and whose passion was encouraging young golfers to play the game well, in its true spirit. These are the shoulders on which we modern Australian golfers stand. Such is the history of golf in Australia.

With generous contributions gratefully received from Alasdair Courtney, Archivist, Scotch College Perth, Malcolm Purcell and Fatima Pandor of Perth, Michael B de D Collins Persse, Keeper of the Archives, Geelong Grammar School, Ms Moira Drew, Museum Curator for Australian Golf Union/Golf Society of Australia and Archivist, Royal Melbourne Golf Club, Graham McEachran of Cottesloe GC History Group and recognising the encouragement from John Pearson, Editor of Through the Green,

Notes

1 The History of the Geelong Golf Club by Gordon Long BA, Dip Ed (Hawthorn Press 1967)

2 In The History of the Geelong Golf Club, quoting Golf World 1957 taken from the St Andrews Citizen

3 Geelong Grammarians 1855-1913 by Justin J Corfield and Michael Collins Persse (1996) page 711

4 Anderson was from St Andrews but he won the British (not world) championship at Prestwick.

5 From a 60 Years on memoir in 1955 by Noel Learmonth (1880-1970) GGS: 1895-98

6 The Geelong Grammar School Quarterly July 1897

7 Geelong Grammarians 1855-1913 by Justin J Corfield and Michael Collins Persse (1996) page 711

8 Information accompanying AGU Museum item; Melbourne GC became Royal Melbourne GC in 1895

9 Building a Tradition – A History of Scotch College Perth 1897-1996 by Jenny Gregory (UWA Press 1996)

10 Obituary by Professor Geoffrey C Bolton quoting Three Schoolmasters Melbourne Studies in Education 1976, S Murray-Smith Ed.

11 Building a Tradition – A History of Scotch College Perth 1897-1996 by Jenny Gregory (UWA Press 1996)

12 From The History of Cottesloe Golf Club 1908-1983 compiled and edited by GH Newman

13 Anderson was one of those who joined the club that night.

14 From The History of Cottesloe Golf Club 1908-1983

15 ibid

16 ibid

17 Obituary by Professor Geoffrey C Bolton

This article first appeared in the British Golf Collector's Society publication 'Through The Green' in September 2005, and is reproduced here with the kind permission of the author.

W. A. Windeyer, golfer: player, administrator and referee c. 1900-1930

The following article was written by AGHS member Jim Windeyer, grandson of W. A. Windeyer. Jim would like to acknowledge the valuable assistance given in the course of his research by fellow AGHS member Don Dunne.

|

W. A. Windeyer entered the golfing scene in 1900 as a member of the founding committee and quickly secretary of the Hunters Hill Golf Club. Of the initial thirty members only four had experience as golfers and he was not one of those. However in 1904 he was the club champion and a member of the team that won the Suburban and Country Golf Association Cup in 1907. On a bigger scene – after all the Hunters Hill course was very short confined as it was to the grounds of the Gladesville Mental Hospital – Windeyer also had some success. He was second in the Hampden Cup in 1911 – although the standard was reported as being ‘very poor, and badly in need of a tonic of some description’.1 The next year he just missed out on a place in the NSW amateur team. However Windeyer’s significant place in the early history of the game in Australia comes from his role as an administrator and referee. Left: W. A. Windeyer in 1926 - champion and captain of Hunters Hill Golf Club (Evening News, 16 August 1926). |

Interclub competition had begun in 1901 when Hunters Hill played Concord. As competition expanded rapidly some overall organizing body was called for. It emerged from Hunters Hill as the Suburban and Country Golf Association in 1902 with Windeyer as secretary for ten years and president for another twenty. In the Hunters Hill club it was acknowledged that his energy and enthusiasm had been instrumental in developing the strong spirit of the club.

Hunters Hill Golf Club - 1901

R. C. Lethbridge, W Davy.

Seated: C. T. Metcalfe, J. W. Hope, H. F. Barton, R. Smith, H. R. Lysaght, F. A. A. Russell, T. Buckland.

Foreground: H. D. Walsh, W. Leigh, H. M. Suttor, C. F. Broad, G. H. Partridge, P. Allan, A. W. I. Macansh,

W. A. Windeyer, H. C. Buchanan, A. J. Stopps.

(Photo courstesy of Mr. Jim Windeyer - click to enlarge)

As secretary of the new organization he immediately brought his energy to organizing the first Country Week in 1902. The success of it can be judged by the final dinner: 100 golfers present and entertainment including Banjo Paterson reading his poems, which ‘brought down the house’, and all present agreeing it was ‘the jolliest golf dinner they had ever assisted in’.

It had all been played in good humour including Windeyer playing one day in a top hat – to win a bet of a sovereign. As reported ‘Mr. Windeyer belongs to the legal profession and he didn’t let that sovereign pass him’.2

Seated: Dr. Littlejohn, W. A. Windeyer, J. Kidd. A. Orr, C. T. Metcalfe.

* The rapid approach of a thunderstorm prevented the whole of the team being photographed.

(The Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser, 12 November 1902 - click to enlarge)

The S&CGA did not include the metropolitan clubs, the Australian and Royal Sydney. Windeyer, wrote the constitution for the NSW Golf Council the umbrella body to cover all; he began as its secretary and treasurer and became its chairman. He really wanted one organization rather than two.

After long delays he produced a draft constitution for the NSW Golf Council and the S&CGA to consider. He was in a strong position, chairman of the former and president of the latter. The NSW Golf Association was born in 1930. The report of the discussion said of Windeyer he was ‘one of the most progressive administrators of golf matters in the state’.3

Competition required rules as well as regulation. As secretary of the council Windeyer approached the Royal and Ancient Club of St Andrews for a copy of their rules and rulings and arranged for their local publication in 1906. To his becoming, as secretary of the golf council and a lawyer, the local authority on the rules was but a short step.

Some decisions he explained in articles in the magazine Golf, Motoring, Tennis and letters to the Sydney Morning Herald. Within a year of the publication of the rules he was explaining the disqualification of E. P. Simpson when he was lying third in the Hampden Cup. No properly signed card had been submitted and in fact a further breach of the rules had occurred when his partner’s card had been retrieved and signed as the rule stated that ‘no alteration can be made to any card after it has been returned’. In conclusion Windeyer expressed the position that was to mark him in all such situations:

Everyone regrets the incident, but it is to be hoped that the publicity that has been given to the matter will induce players generally to acquire a better knowledge of, and to more rigidly adhere to, the rules of the game.4

Another letter concluded, ‘I would ask, why should not the rules be adhered to as strictly in golf competitions as they are in billiard competitions?’5

Two months later the issue was not third in the Hampden Cup but first in the Australian Championship. The Honourable Michael Scott finished eight strokes ahead of the next player, Dan Soutar. On one hole Scott had teed off from outside the teeing ground: a technical error from which he gained no advantage. But the rule was clear, ‘If a competitor play from outside the limits of the teeing ground, the penalty shall be disqualification’.